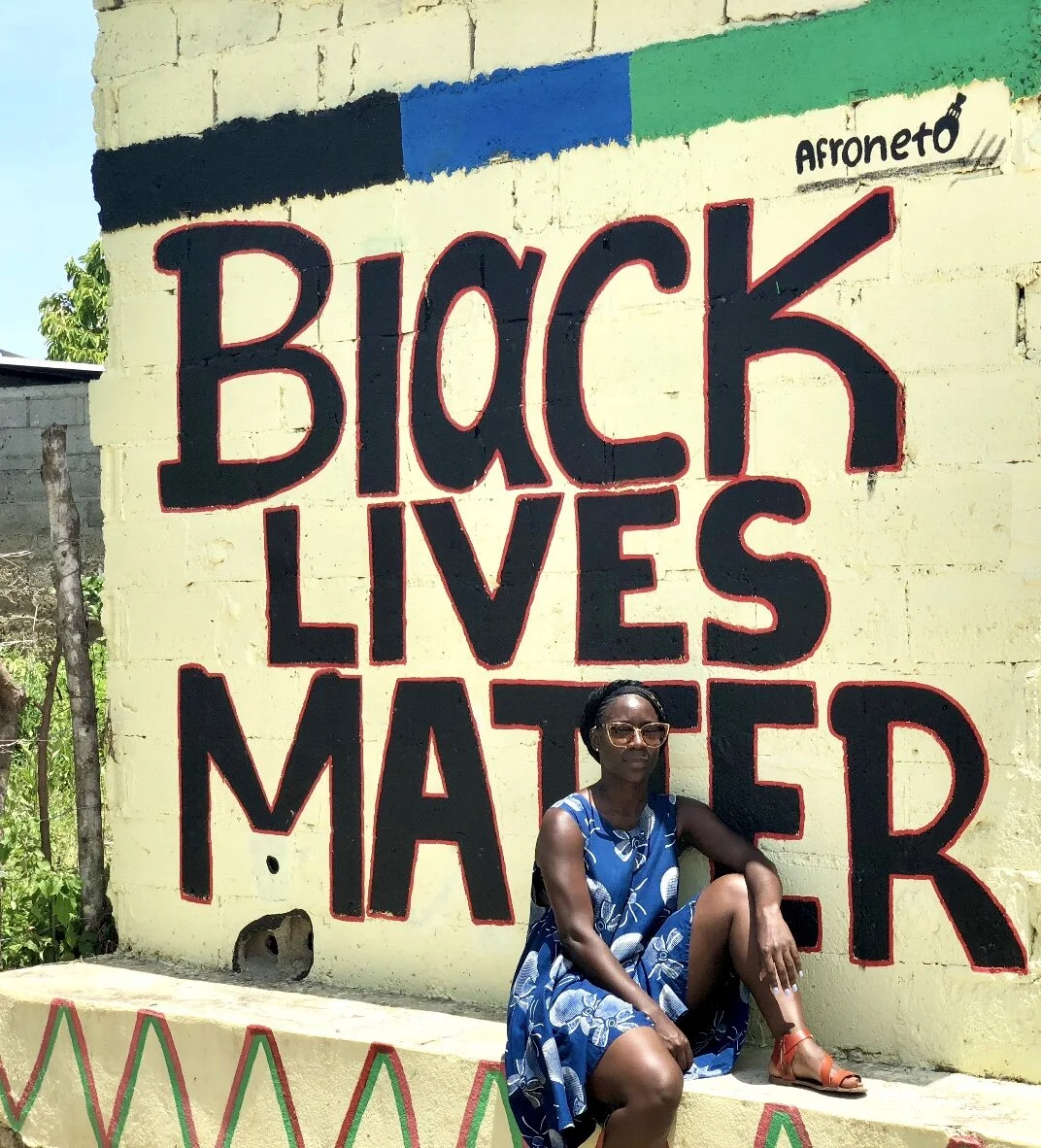

Mounia Asiedu, Math Teacher

Hi, Mounia. Thanks so much for doing this. We’ll start with the basics. Can you tell me what you do?

I am and have been a teacher for 8 years. I’m also a part-time graduate student pursuing a Master’s in School Counseling.

And so how did you come to be a teacher? I know that’s a big question.

It’s kind of a long story, but I think that I’ve known that I wanted to be an educator for a good while -- at least since before I attended college. Unfortunately, I made the mistake of not following my heart and took the long road to get here. I’m a second generation American who was raised by a single mother. Just to give you some context, we lived in a three-bedroom apartment in Flatbush with other family members and at any given point, there were at least 13 of us living there. You can imagine that when we had conversations about future occupations, my mom’s main concern was how I would be able to take care of and create a better life for myself. The push definitely wasn’t to become a teacher. It was either you became a doctor, a lawyer, or some kind of business person.

When I finally attended college at Temple University, I double majored in legal studies and international business administration. During my junior year, I had my first opportunity to teach through an Americorps program called Jumpstart, where I worked in a pre-kindergarten classroom with students from underprivileged backgrounds. I loved it, but I knew that it couldn’t pay the bills.

After I graduated with my Bachelor of Business Administration, I moved back to New York and worked at a non-profit within the criminal justice system. I often describe it as soul-crushing work. For three years I worked as a Release on Recognizance (RoR) interviewer and I watched defendants who were a majority Black and Brown kids, being shuffled in and out of cells, shackled in arraignment courtrooms, and treated in some of the most unfair and inhumane ways. At a point, I took some time to reflect and I came to the conclusion that I wasn’t a part of the solution for these kids. The thought of that wore me out and ultimately, I had to make an exit. I decided to apply for the New York City Teaching Fellowship program in 2012 and I’ve been in the classroom ever since.

I think it’s interesting that you worked in the court system because having been in public education administration myself, the school to prison pipeline is something you constantly hear about. How did what you experience in your role as an RoR interviewer influence how you approach teaching? I’d imagine you would implement a kind of counterbalance to the justice system’s very deficit-oriented way of viewing black and brown students.

The school-to-prison pipeline is very real! I remember interviewing so many kids and overwhelmingly, most of them had not graduated high school. So many of them had stories about being pushed out of school. I think that my background offered me very unique insight on what the other side could actually look like for my students and there is no way that I could ever want that for them. So, I have always tried to keep that in mind. I try to remain hyper-aware of what the consequences of suspensions could be, of what a classroom removal could lead to for my students. Additionally, the data is out there that shows that these things don’t work, so why would I utilize these tactics?

What we know works is fostering meaningful relationships with your students. We know that restorative justice programs and efforts are more effective than suspensions and harsh disciplinary actions. What has the potential to work is keeping love and care for your students at the center of your practice. For me, that has been the way that I have been able to connect with some of my toughest kids. It was never through isolation. I want them to know that I will hold them accountable and even when we struggle, when we don’t agree, and when they don’t like me, I’m still going to love them and be right there for them the next day. Also, I think it helps that I’m a Black woman teacher who is from Brooklyn just like them. I’m familiar with their neighborhoods and we have some stories in common. I believe there is truly something powerful about representation, visibility, and feeling seen.

You spoke about being heavily encouraged by your family to go into certain careers -- medicine, law, engineering -- which ended up not being fulfilling. That emphasis on STEM careers is one that I think is probably familiar to a lot of immigrants, or children of immigrants, or even just African Americans who are focused on upward mobility. It’s this gold standard. As a math teacher, how do you alleviate that pressure to excel in math or STEM, and allow your students to really lean into other subjects they might be passionate about?

I think that I’m still learning and evolving in this area. Given the structure of our deeply flawed education system -- one in which students’ standardized test scores are tied to your overall teacher rating -- a lot of educators, especially those who may be untenured, are forced to prioritize these subjects. It’s extremely intimidating and to be honest, it wasn’t until I received tenure during my third year that I felt a lot more comfortable with the idea. As weird as this sounds coming from a math teacher, my main focus is no longer math content itself. This isn’t to say that it’s not a focus, because I definitely love math and want my students to also love it. I just think that before we can get there, before I can ask my students, most of whom have not had a great relationship with math in the past, to dive in and even embrace it a little bit, we really need to build on some other things.

I have the luxury of being a part of a program in my school that allows me to have some of my former students as teaching assistants in each of my classes. My classroom is structured around relationship-building and working on skills like resilience, critical thinking, and questioning, first and foremost. Students complete their work mostly in groups and learn that success can’t be experienced in isolation. They learn to depend on one another and I try to instill in them the idea that they are responsible for each other. We operate as a unit. These are skills that I believe can extend beyond math class and will help my students in whatever fields or trades they decide to enter in the future. Over the last few years that’s where I’ve focused my energy, on building a community.

Who are some of the role models or influences you’ve had that have helped you shape your approach?

Ooh, several! So I am fortunate enough to work in a school with administration that understands the importance of the whole child, versus seeing a child as a test score -- as a one, a two, a three, a four, or as a pass or fail. I’ve had a lot of support through my principal -- thank goodness -- and my assistant principals and some of my colleagues who were there before me and have dedicated their lives to empowering children and fighting racism through education.

And what are some of the things you’ve learned from them? Key take-aways or lessons they’ve imparted on you, that you continue to return to in your career?

At my school, we have two unofficial slogans, “An injustice to one is an injustice to all,” adopted from words spoken by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Also, we say “We are all working on something.” Both are constant reminders that as an educator and as a human being, it is my job to continue to work towards equity and creating opportunities for my students to be successful. My students and all students are deserving because they are here. Period. Anything that goes against that idea is worth fighting against. When I’m feeling inadequate as a teacher and generally overwhelmed by how brutal our world can be, I return to these words for purpose and hope. They keep me going and remind me that you don’t stop. You don’t give up. This work is extremely important and we all need others who will continue to show up for us, especially our children.

You said you were in a graduate program. What is the program?

I’m at Hunter College right now for school counseling. So this is interesting. Applying for the program came about similarly to how I got into education. I can't remember exactly what it was, but some big world event had just taken place. At this point, it seems as if there is one every day. I’m going over my algebra lesson and looking out at my students and I had a moment of pause within myself. I thought “Why am I doing this? Why does Algebra matter in this moment when our world is on fire? Why does this matter when some of my students are going through some extremely traumatic stuff in their everyday lives?” I think that every few years I have these periods where I start to reflect and re-evaluate whether or not I am doing what I need to do to be helpful to my students and to others. And so like my experience with my role in the courts, it came to a point where, yes, I love math and I love teaching, but I see myself being able to support students in a different way, in a way that I believe is a bit more meaningful right now. Given the state of America, and the entire globe really, it’s hard not to think, “Why am I standing in front of students talking about equations?” For me, being a math teacher is limiting at this point. I’d like to devote more time to helping students navigate issues in their lives. I want to have more conversations with them about what’s going on in their worlds and the world at large and help them to find ways to be a part of a solution.

What do you do to make sure you keep your own mind right?

Woo! (laughs) First and foremost, I spend a lot of time talking to some of my colleagues who have been in education for a long time. The individuals that I call my friends at work have a firm grasp on why we’re doing this thing -- they get it. I can turn to them with questions or when I just need to vent. Oftentimes, that’s my therapy. Recently, I also started to do a lot of reading for my own pleasure again. I listen to lots of music. I meditate, and use a singing bowl to clear my mind and center myself. And traveling! Having summers off is a great thing. I go on a solo trip every summer and it does wonders. I always come back feeling refreshed and renewed. Lots of meditation, positive affirmations, reciting mantras, all of that stuff.

In your career as an educator, what has been a misconception you’ve uncovered? Or an “a-ha” moment?

That teachers, or even adults for that matter, have the answers. In fact, I believe that young people are the ones that have the answers and that we need to listen to them more. At any point in history, they have been at the forefront of movements for change and progress.

And what have you learned from your students?

To be patient. To be humble. (laughs). I’m trying to remain teachable and open to feeling uncomfortable. More and more, I’m embracing the idea of giving up my power as a teacher to empower my students. That definitely was not my experience as a student and not what education typically looked like when I was growing up. I don’t know it all, even with these degrees. I’m taking my cues from them and I’m really just learning to listen.

Since we’re on the topic, what are you excited about for the future? For yourself, for the world, or for your students?

Just the idea that change is in motion. I think that we can very easily get wrapped up in the notion that things should happen quickly, but if you know anything about change, you know that even though it may be slow to come, it comes. I trust, knowing my students, that the world is going to move in a more progressive direction. It will move towards a place where people are free to be themselves, a place where we’ll have less hate in the world, and more people will be caring and loving, and interested in the well-being of the collective rather than the individual.

Awesome. So, finally, I like to leave a space where you can share anything we didn’t get to that you’d like to put out there.

We need more Black educators and more diversity in the classroom (laughs). We definitely do. It’s important for students to see themselves. I hope that soon we get to a place where we really make representation and equity in education a priority.

Yes! I’m really excited for you to become a counselor because what you’ve shared about how you think about your students, and how you view them so holistically as these beings in constant transformation and with infinite potential, I’m so glad you’re in front of them at this time in their lives. To have a counselor who can speak to the socio-emotional side of education, who has a shared background is just so rare.

Thank you! And thank you for doing this project. I’m excited for you. It’s admirable that you’ve taken on the incredible task of highlighting the everyday Black woman in her field of work. I think we have a tendency of assigning value based on who is in the spotlight and who isn’t. The truth is that every single one of our stories matter and deserve to be told. I hope this project encourages many more of us to do just that.

I appreciate that! Thank you so much, Mounia!

Please share this post with a friend, and follow us at @BlackWomenWorkIG!